The Worst New Guys In History

This is just some dumb shit I’ve been musing on, but I think it might be healthy to type up some of these errant streams of consciousness. My normal process is to force these thoughts on some FNG on my boat, who has no choice but to sit their and listen to my infinite wisdom, lest he upset me and I curse him into endless dinq-ness.

Today I’m thinking about programming, and why people who want to learn programming are among the worst learners in history. If you’re a programmer yourself this post will come across as obvious or pretentious, depending on how you feel about the topic.

Background

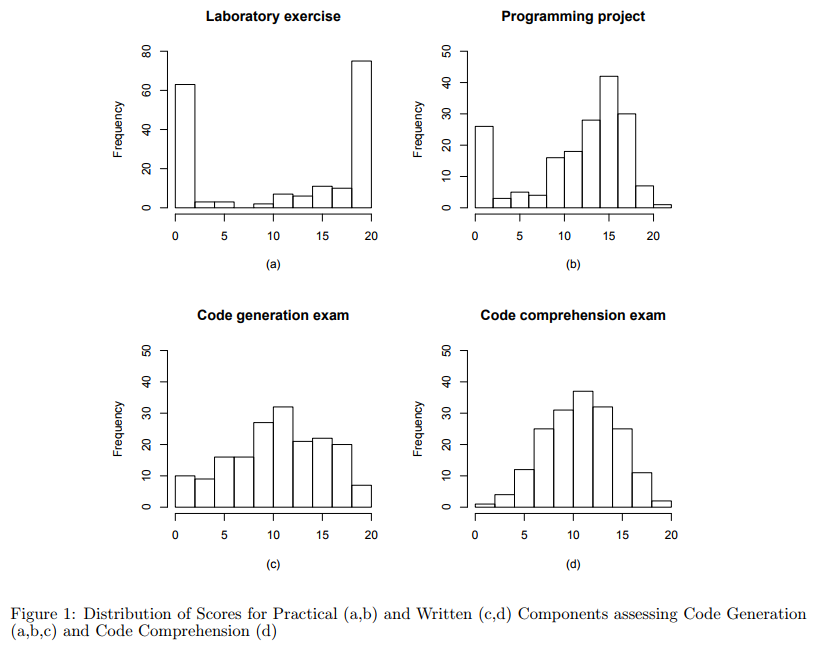

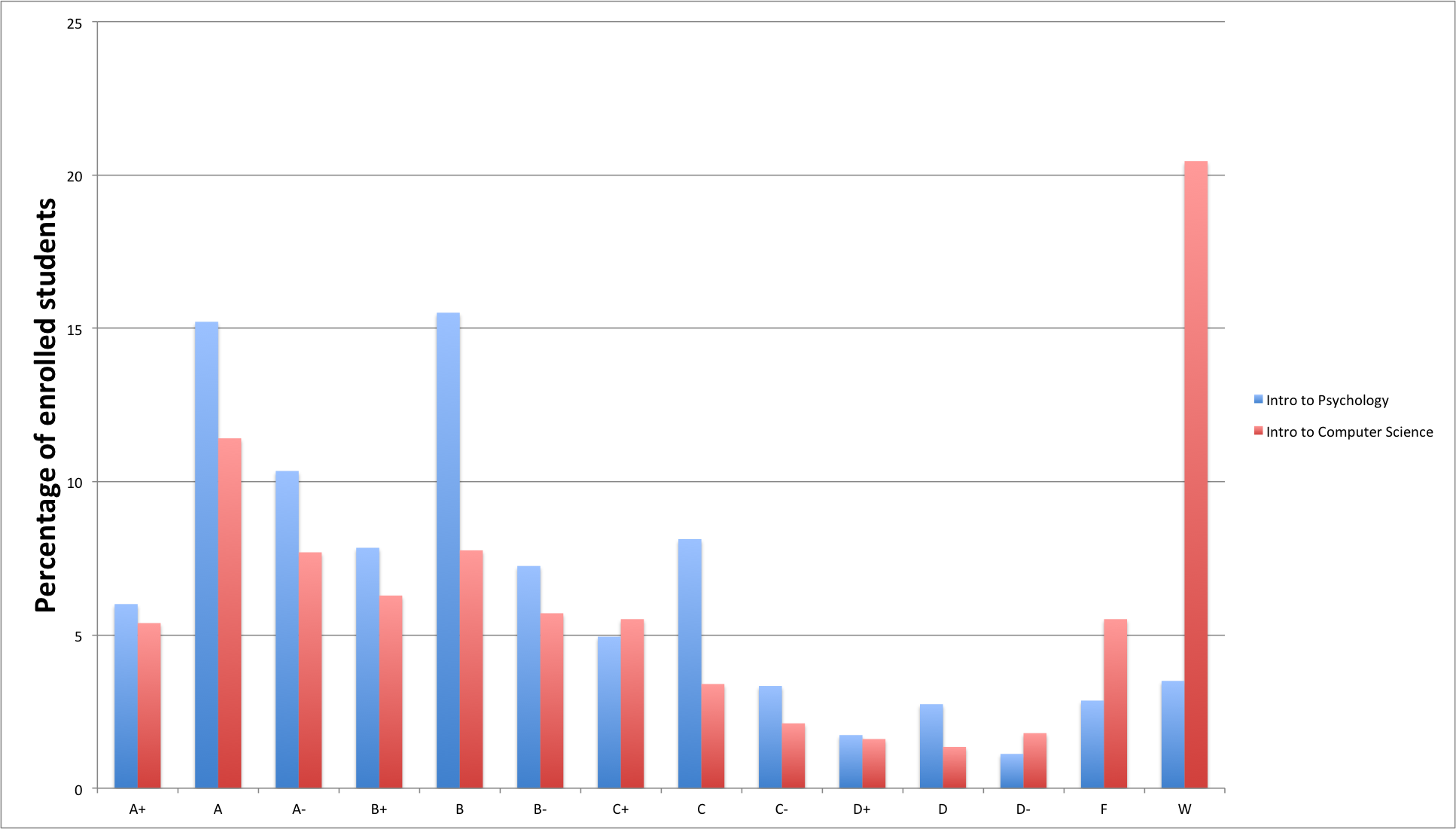

Learning programming is hard. That’s not an opinion, there’s a lot of well established literature around the fact that Intro to Computer Science students seem to fail at staggering rates. 1

Historically this phenomenon has been called “the camel has two humps”, after a line from an unpublished and now unpopular paper from 2006. The data doesn’t seem to bear out that Intro courses display a larger bi-modal distribution than introductory courses of other fields. However, students definitely drop out of Intro more than other fields. 2

Thus ends the section of this blog post with anything resembling science or facts. Now enter wild conjecture and speculation, I propose that as a creative pursuit programming is harder than most other fields that have come before it in human history. I further propose that the usual approaches of self-teaching programming are antithetical to productive knowledge, and if you want to learn to program you should build a video game. Let’s go.

Programming is Art

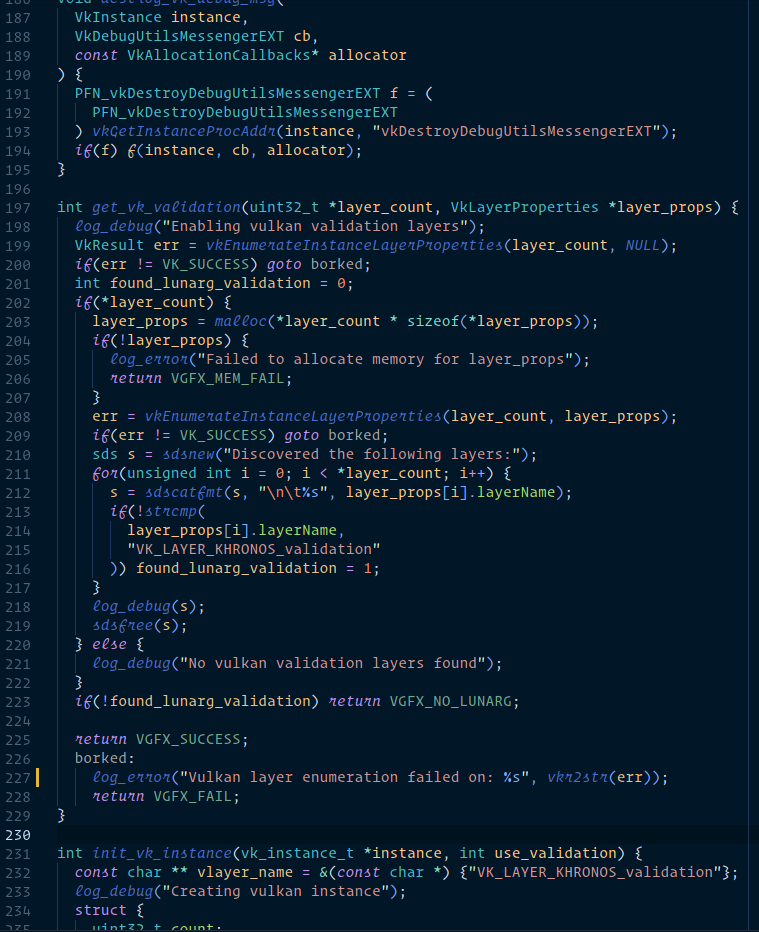

Leaving aside the usual question, programming inarguably demonstrates some key aspects we associate with creative pursuits. One I’d like to touch on quickly is coding style, a source of endless debate among programmers. I hesistantly offer up this screenshot of my editor. You don’t need to know anything about code, just get a visual impression.

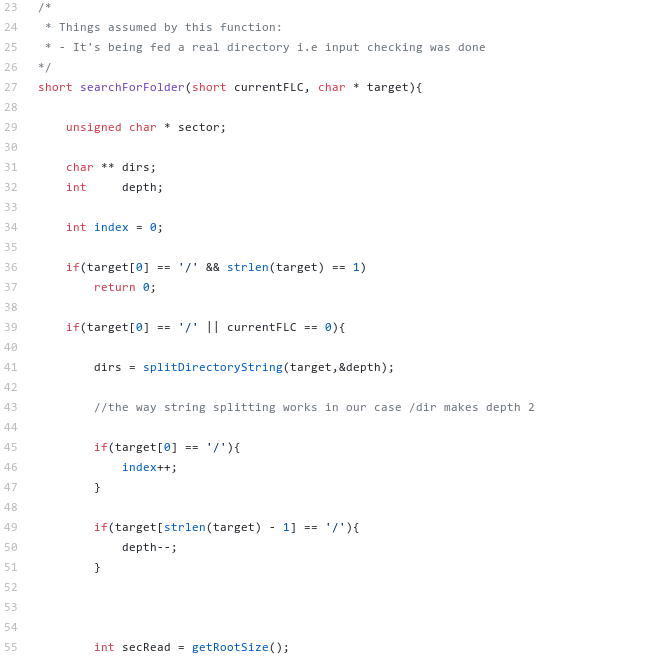

I’d like you to compare that to some code in the same programming language from my good friend Alex.

We see a large contrast between styles here. I value high information density, struggling to hold in my head what I cannot see on the screen. In order to manage and organize this writhing mess, I’ve configured my editor to semantically highlight the code. This hijacks the brain’s visual processing pipeline and allows sufficiently maladjusted people like me to navigate the code the same way most people can identify different ingredients in a fruit salad.

Alex exists at the opposite end of the spectrum, his dominant organization pattern is spatial. When I send Alex code to review, the first thing he does is carefully read each statement and insert blanks every few lines. This process of organization gives him the information he needs about the program, similar to knowing the contents of the drawers and cabinets of your house by having each collect a related group of objects.

Both Alex and I are achieving the same thing. We’re using established cognitive pathways to map code to an internal model of computation. That internal model is where I believe many people struggle.

Code is Not Programming

Imagine for a minute, an aspiring writer trying to develop her skills and eventually publish a novel. She does lots of research, buys a typewriter with great reviews, settles down with a dictionary and a thesaurus, and begins to type every single word in the English language. As she types she looks up the words in the thesaurus, and learns all the relationships and colloquialisms. She studies grammatical rules in the evenings, and maintains decent penmanship in case she ever needs it.

What effect will this have on the quality of the writer’s novel?

Consider a second author who spends the same amount of time reading great works of literature, and writing her own stories.

Who’s novel will be better?

If you think the example is contrived, this is exactly how many online tutorials teach people to program. They focus on the tools of the trade to the complete exclusion of the trade itself. With programming, the trade is computation, and a consistent internal model of computation is necessary to build non-trivial programs.

New-comers to programming frequently ask questions about how to do impossible or near-impossible things. Their lack of an internal model means they don’t have the ability to even put bounds on their problem. A comparison would be an apprentice carpenter asking which saw to use to bind two pieces of wood together.

Programming is Different

Why doesn’t the carpenter need an internal model of wood? Or writers of story? Why don’t we talk about artists needing an internal model of cubism?

Because each and every one of us already has those models. They don’t need to be developed from scratch, “merely” refined from their amateur state.

The written word is a couple millenia old, art a couple millenia older than that. Jury is out on what came first, grammatical language or story telling, but probably story telling. Physics has a basis in human experience, so does math, chemistry, biology, and most other scientific fields.

Which is to say you already understand these things, at some extremely basic level at least, along with everyone else for all of recorded history. A student of art might find the style and tastes of a layman to be bad or simple but the layman still has tastes. A newcomer to computer programming lacks even these foundational elements, because to have taste they would have to know what the hell it is they’re looking at.

How to Learn Programming

Despite all that whinging, I don’t believe learning to program is any sort of herculean feat. I just wouldn’t advise ever reading a programming textbook cover to cover. The goal of the beginner programmer should always be the development of practical, useful programs. These programs will rarely accomplish what they were originally planned to do, but in the process of failing beginners will place the cornerstones of intuition necessary to succeed.

A carpentry apprentice doesn’t aimlessly cut wood, he purposefully attempts to build furniture and learns in the process of failure. My only piece of practical advice in this entire post is that video games are great pieces of software to fail at building, because they cover a wide swath of programming challenges and you get to have some fun along the way.

Every question must be relentlessly pursued to ground, assumptions should be constantly challenged. Students should never accept “because that’s the way it is”, the most they should allow is “we’ll get to it later”. Reason being, false foundations lead to those impossible questions, an inability to frame problems and their solution space.

Professional programmers don’t do this of course, they happily accept black boxes the same way soccer moms accept that their vans go vroom when they push the accelerator. The difference is the professional programmer has already developed her intuition, she already has a consistent internal model of computation, and therefore can make reasonable guesses about how any given black box works. Just like we can make reasonable guesses, broadly, about how the accelerator in the van works.

When a beginner finds she’s naturally making those kinds of abstractions about how computing works, she is no longer a complete beginner and can proudly call herself a rank amateur.

Conclusion

This whole piece is kinda crap, if you’ve read this far I want you to know I recognize that. I vaguely point out that new programmers have a hard time, make a gonzo claim about why, and offer two and a half paragraphs of solution.

The point I was trying to get across was simply this, learn how computers work before trying to “master” a programming language. The best way to learn how computers work is to write a lot of code and ask a lot of questions, and be relentless in your pursuit of answers. Everything else is shit or product placement.

-

Source for graphs: https://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2459943 ↩︎

-

Source for graph: https://psychology.stackexchange.com/a/9509 ↩︎